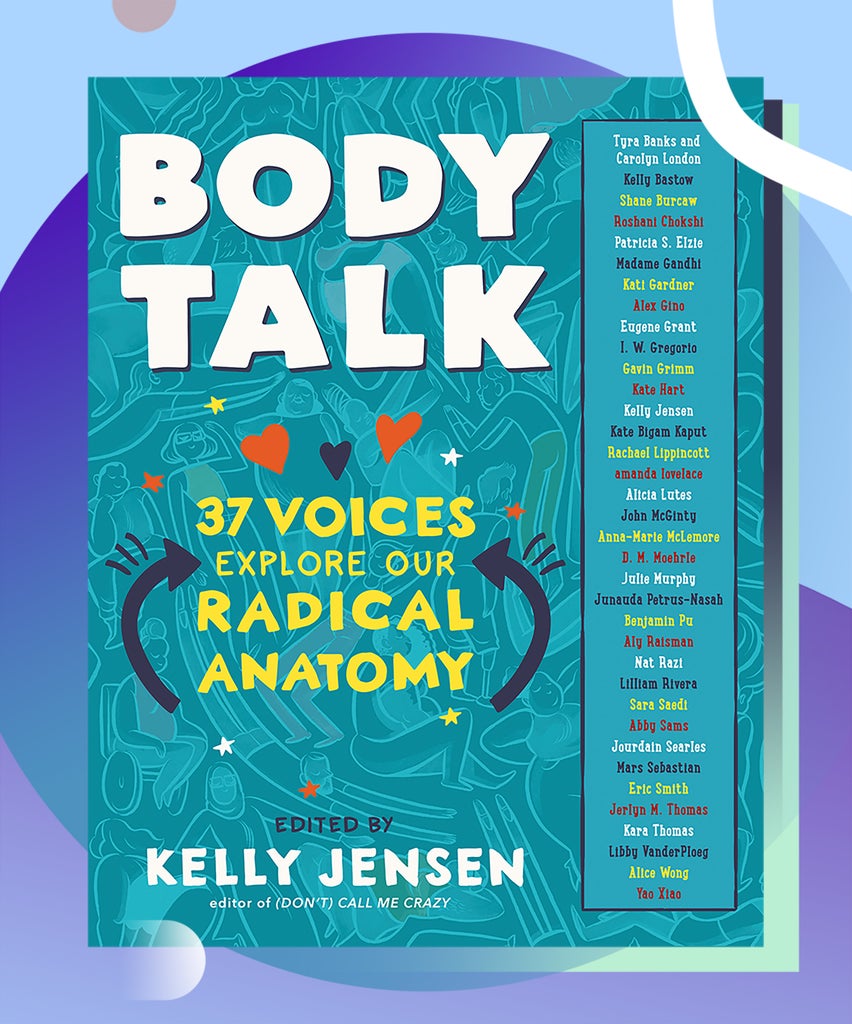

Author and editor Kelly Jensen is building a career based on helping young adults feel more comfortable talking about complicated issues relevant to their lives, subjects that have been difficult for parents to discuss with their children for generations. Her past books have tackled topics including feminism and mental health. For her new anthology, BODY TALK: 37 Voices Explore Our Radical Anatomy, out on August 18, Jensen collects 37 essays that all focus in some way, shape, or form on body image. In an exclusive excerpt from the book, Junauda Petrus Nasah discusses race, queerness, and self-acceptance.

“Junauda, are you ashamed of your body?” my mom asked me one morning. I was about 12 years old, getting ready for school, and we were in the bathroom of our small house. I was taking a bath in our clawfoot tub, laying on my stomach to hide my developing body from her opinionated eyes, and she was peeing. (Modesty or privacy was never an option in our home of mama and her four daughters and one bathroom.) I told her I wasn’t ashamed of my body, and I was lying. But I knew that was what she wanted to hear.

She saw right through my response and continued her inquiry.

“Junauda, you should love your body. I wish when I was your age that I knew how beautiful my body was.” She spoke with a regret that made me pay attention. In that moment, I tried to imagine my mom as a girl like me, having feelings about her body. I was in the cooling bathwater, hiding the signs of my impending womanhood, while my mom, a Trinidadian woman with dark skin, striking features, and an impenetrable self-esteem, even in this inglorious throne, implored me to see myself as stunning and complete. This moment, in all of its awkwardness, left me with a seed of insight: that I should love myself — love my body — even if it didn’t seem possible then.

My mom didn’t know what I was navigating in my middle school life. Every day in 7th grade in 1993 was like hood fashion police. Deonte wearing the same pants as yesterday! Look who got on sneakers from Payless? Junauda got hair too nappy for relaxers, pink lotions, and hair gel! Who got high-waters on? Rapheal try to be like Kriss Kross, but got tight-ass, high-water overalls that he wear backwards with one strap swinging and look busted? Who got socks with holes in it? Who in this classroom had sex before? Who smelling all musty and ain’t put on deodorant? Who ain’t matching? Got plaid and paisley on and faded hand me downs? Who got a hairstyle look like they in the 3rd grade? These questions posed by popular and grown-ass 8th graders during any given class — where were the teachers? — always stressed my young soul with panic.

My clothes were always unremarkable, faded or hand me downs, and I had never kissed anyone (although I had an elaborate lie involving Raphael ready to spill if I was ever asked). I was always anxious I would be pulled into these interrogations. My family’s economics and immigrantness and my awkwardness added to the challenge of me fitting in, so I stood out as one of the frequent targets. I had desires for boys in my school who would never see me as pretty, and I had desires for girls, too, something I was curious and simultaneously ashamed about and hid away from myself and the world. School sucked so bad sometimes, I would beg the hall monitor to let me sit in her office to avoid being teased for my hair and my nerdiness.

But in 8th grade I decided to stop trying to make my older sister’s hand me down Girbaud and Cross Colors into an identity of a kid who wasn’t poor and, instead, I started to dress grunge. I had been inspired by a White girl who was in band with me, who started skipping school and dying her blonde hair a new color every week with Kool-aid. She stopped caring what everybody thought and somehow that seemed like the answer for me. To not care what folks thought and indulge in the path of the outsider.

By that time, Left-Eye from TLC, Aaliyah, Bjork, Claire Danes, and D’arcy from the Smashing Pumpkins were among my style icons. I crushed on their androgyny and quirkiness, how they seemed to define their own kind of power and sexiness. All of them beautiful and irreverent, but also not quite like me. I listened to Alternative music that reflected the Black Girl Emo that hurricaned inside of me, the one that no one seemed to care about. My mom was mortified when I would dress like I borrowed somebody’s grandpa’s favorite bingo outfit after he was attacked by piranhas. “You finish dress?” she would ask every time I would present my newest outfit. After I’d affirm yes, she would offer her opinion.

“Junauda, White children wear dem clothes, and people see it as a style. YOU wear dem clothes, they think your parents is poor, or we ain’t care about you.” The Caribbean parent backlash was real. My mother couldn’t understand why I would purposely try to look raggedy. Was this the American dream she had worked so hard for? But I loved how I looked. It felt powerful to look like I didn’t care what anyone thought, even though I did deeply.

My eight grade year, my boobs were coming into formation. I was growing pubic hair and a thick ass, and every jerk on my block and at my school noticed and would holler some dumb and sexist insight to me about my body — my body that I was already devastatingly self-conscious about. In the early 90’s the fashionable bodies were “36-24-36,” a rare and sexualized ratio of bust to waist to booty. The other body type popular in media was to be so skinny that your hip bones and rib cage were visible, with no boobs or booty at all. Teen magazines, boys at school, men in my neighborhood, other girls at school, and the music videos I was watching, from hip-hop to grunge, all told me I had to prescribe to a specific body type to be lovable. This was also when I first learned about eating disorders, which seemed to me like a symbol of privileged and white girl angst. They never felt relevant to me, even though shame and unhealthy habits, like eating sugar for comfort and extreme dieting, were settling into my psyche in insidious ways that would take years to release.

Brown and gap-toothed, I couldn’t see the beauty in me.

By the time my mom had spoken to me in the bathtub in 7th grade, I had already internalized messages about my value and beauty in my femmeness and Blackness. When I was five, I have a vivid memory of ripping up my kindergarten school pictures, because I thought I was so ugly. I was young, but I’d be lying if I said I didn’t feel that way, with all my little heart. I had been playing with blonde Barbie dolls, my dad had left my mom for a White woman, and those things along with other messages I was getting about my Blackness from society and school, made me start to look at myself harshly. I was constantly in battle with my relaxed hair, which despite the calming description of the process, burned my scalp, forcing my natural coils into brittle straightness. (I eventually went natural at 15, inspired by Lauryn Hill, and rocked a little Afro.) As a teenager, I hid in my grunge and hip-hop inspired uniforms of plaid button-ups, headwraps and baggy jeans. This was a time in my life that I just wanted to disappear, and it seemed, instead, that more of me was appearing, growing, and maturing.

When my mom was 15, she became a mother for the first time. She was a little older than I was that morning in the bathtub. She would tell my sisters and me that she loved us and also that she hadn’t been ready to be a mom when she became one. She would remind us that we could choose whatever we wanted for our future, that we were individuals, that our bodies belonged to us. In other ways she would also remind us that the world had ideas about who we were. Whether she was praising or critiquing us, there was always a harshly earned knowledge about what it means to have a Black femme body in this world.

My heart and body were mine, and they also belonged to a line of women whose bodies were abused, overworked, sexually violated, and stigmatized for generations. Yet, they still found pleasure in love, dancing, and expressing their beauty through intellect, movement, and adornment. My heart and body were mine, yet walking around as a teen girl felt vulnerable, scary, and depressing.

Over the years my body has experienced my life with me and absorbed my feelings about myself. And I have under-loved, disrespected, hated, disregarded, and harmed myself. I have starved myself for thinness and ate until the point of vomiting when I was pushing down my feelings and anxiety. I have hated and critiqued my body and believed that was the right relationship to have with it. I’ve desired to contort into a form I believed would be more lovable to this world. I forgive myself every day for this and try my best to replace these feelings today with sweetness.

Healing is traveling back in time to meditate and love on the spirits of my younger selves and my ancestors. The selves who struggled with worthiness and violence, so that I could love myself and accept the individuality of my existence and magic. I look at pictures of me at different ages, 5, 9, 12, 15. I look at my selves, my Black and dreaming selves, and see the insecurity and doubt in my eyes. I speak lovingly with my younger selves and tell them they were always deserving of love, from myself and this world.

My body has been a sacred shape-shifter and a devoted temple to my beingness, and I didn’t love it as much as it deserved. It has danced until the sun came up and run from danger and fought for my sisters and me when I couldn’t run. It has flung itself in the sky, submerged into deep oceanic waters, and tasted some of the most delicious meals the planet has to offer. My body has experienced pleasure and cruelty from lovers and myself. It has held my emotions, my undeniable and passionate truths, and the parts of me that need to be heard.

My body has been a vessel for those expressions.

These days I ground in meditations of love for my body, my face, spirit, and soul, I take time to look in the mirror and practice acceptance of me. I look at my whole body and drink myself in slowly. I practice redirecting my spirit to loving on me. I seek to unlock portals of pleasure, peace, and insight that I deserve to experience on behalf of my ancestors. In these meditations I think about that seed of self-love my mom planted in me on that early morning in the bathtub in the nineties. When I barely knew my body. Today, I smile to myself, grateful for her gift and the mantra to love on my body with unbelievable inquisitiveness and reverence.

From BODY TALK edited by Kelly Jensen © 2020 by Kelly Jensen. “Loving On Me Is Prayer: Queer Journeys into Black Girl Self-Love” by Junauda Petrus-Nasah © 2020 by Junauda Petrus-Nasah. Reprinted by permission of Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. All rights reserved.

from refinery29

Body Talk excerpt: One Writer’s Path To Learning To Love Her Black Femme Body

![Body Talk excerpt: One Writer’s Path To Learning To Love Her Black Femme Body]() Reviewed by streakoggi

on

August 11, 2020

Rating:

Reviewed by streakoggi

on

August 11, 2020

Rating: